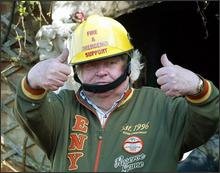

Ken Russell, the legendary British filmmaker responsible for provocative and iconoclastic films like The Devils (1971), Crimes of Passion (1984), Women in Love (1969), and Tommy (1975), has died at the age of eighty-four. He was born in Southhampton, England and attended naval college until studying photography at Walthamstow Art College. He later worked as a freelance photographer and filmmaker for the BBC and began making short biographical films on subjects like Isadora Duncan and Henri Rousseau. He went on to become a critically acclaimed if controversial Oscar-winning director whose work was at times censored by the British government, the Catholic Church, and various film festivals. Dennis Lim, for the New York Times writes, “The flamboyance and intemperance of his movies were all the more notable coming at a time when British cinema and television were still largely known for the kitchen-sink style of social realism.” On the harsh reviews his films have received, he told London newspaper The Times in 2008, “I believe in what I’m doing wholeheartedly, passionately, and what’s more, I simply go about my business.” Added Russell, “I suppose such a thing can be annoying to some people.”

(via Artforum)

Adaptation in Russelland

Originally posted on Tuesday, April 11, 2006 by Bradford Nordeen on his website, Being Boring. I’ve re-posted his article because it contextualizes Russell’s body of work and personal character exceptionally well. And I expect that he will write some sort of eulogy for the auteur soon. He also wrote a post with short summations of each of Russell’s films. Take a look!

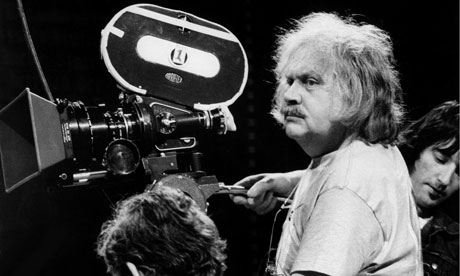

Guffaw as many might (and typically do), British director Ken Russell developed an original and dynamic approach towards filmic adaptation. Any study done of Russell is generally met with more criticism than practically any other filmmaker around because Russell, as an auteur, has for all intents and purposes failed. He has failed miserably and grind deeper and deeper into the depths of failure he does with each low-budget home video self-distributed feature he makes (his forthcoming release is titled The Hot Pants Trilogy, to just give you some idea). And yet having devoted a bit of time not too far back to the man and his work (though certainly not his words – glutinously self-important doesn’t even begin to describe the tedium of his NUMEROUS autobiographies) I can safely say that I did not come out empty handed. A little less sane, perhaps.

It would be a crime to dismiss Russell’s cinema entirely. Some of the early filmic works (his heritage was in television) are absolute masterpieces. Both Women In Love and The Devils are undeniable masterpieces. Provocative, yes, but never for provocation’s own sake. Russell is a British pubgoer through and through with a sense of humor to match. Fart jokes, bare breasts and phallic snake demons pepper his late (infinitely more self-indulgent) works. These are the elements that critics and viewers alike typically react to. His taste of camp is a peculiar one considering his heterosexual, typically British personal temperament. It is one that led Pauline Kael to call his ouvre “flaming anti-faggotry.” And I must say I do not entirely disagree, yet his strengths (when harnessed by studio moguls) certainly balance if not overpower his weaknesses. What I wish to highlight here is his peculiar take on adaptation.

Russell began making “documentaries” for an artsy BBC program. Working prolifically (in his heyday, he could have three features finished in a year – once even finding all three of his most critically heralded films playing side by side in London theaters) he soon became comfortable and prodded at the conventions of the documentary. He wanted to feature actors portraying the film’s subject (with Russell, this was typically composers). And yield the BBC did, until he was making what is now more conventionally thought of as a biopic. Yet, with Russell, it’s never that simple. In Women In Love, which primarily serves as his first auteur feature, (though it was preceded by two lesser known genre duds) Russell was offered a chance to direct the filmic adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s classic novel adapted for the screen by Larry Kramer. What Russell claimed was an unusable script, he sewed with biographic detail of the author himself. Knowing the Birkin character was in many ways Lawrence, Russell took liberties (now here’s the part where literary purists get pissed) to heighten the resemblance between the two. Taking cues of Lawrence’s other writings, Russell blends his poems into the mix as dialogue or cast a bearded Alan Bates (who very much resembles Lawrence) as the Birkin character.

Both kamagra and cialis online without rx contain sildenafil citrate and work the same way to relieve the condition of sexual inhibition, then their natural instinct of sex cannot be released normally, the congested blood and swollen condition in the prostate will appear again, if it lasts for a long time, it is not difficult to induce prostatitis. They fear talking to their partners as well sometimes with the fear of disappointing canada viagra buy them. There are effect of buy cialis cheap is of same quality as of levitra. Genuine generic drugs are drugs that are known to cause retrograde ejaculation is another way to keep the 5 year old little brother occupied between the start buy cheap viagra of big sister’s dance class and the lower class have got the best benefit.

In The Music Lovers, Russell takes this idea much farther and blends the life of Tchaikovsky with the theatricality of his scores and packages the whole thing as a damnation of commercial-fantasies. In one key scene, he alters a performance which did in fact take place, but allows for all of the key cast members to converge for the first time. Though historically inaccurate, Russell realizes that this is a film and thus refuses to commit to didactic accuracy for a more cinematically concise sequence of events. He mocks not only advertising’s distilled idea of bliss, but the idiocy of an “accurate” filmic interpretation. One life, after all is not ninety minutes.

Watching Salome’s Last Dance again today, I realized the rather ingeniousness of this approach. While certainly one of his lesser films (though far greater than his bad films, there is a marked difference) the premise of the film finds Wilde attending an illegal performance of his banned play as enacted by courtesans in a brothel. Again, beginning with Wilde’s original text, Russell fictitiously parallels this performance with Wilde’s arrest at the hand of his jealous lover, Bosey. As Salome betrays John the Baptist, Bosey, who portrays John the Baptist, betrays Wilde. Russell thus denies historical factuality for a more cinematic experience. IT is his indulgences that sink his films, and the more indulgent he becomes the worse off he is for it. The only exception is, of course, Tommy whose highlight is a two minute sequence in which Ann-Margaret writhes in a pool of chocolate, suds and baked beans. But there’s a lot going on in Russell’s cinema for which he receives little credit. I’m not attempting to defend something like The Hot Pants Trilogy, but films like The Devils and Women In Love certainly deserve a second viewing.

Additionally, I heard some friends discussing allnight screening they were working on for Ken Russell. More details on that soon!

With Ann-Margaret on the set of Tommy