Mauricio Kagel was a German-Argentine composer who was most interested in the theatrical side of musical performance. Deploying a critical interrogation to the position(s) of music within a cultural matrix, Kagel’s practice was sutured between and strengthened by other disciplines; mainly cinema and photography.

Perhaps the least well known of the great post-second world war avant garde composers, only Luigi Nono was comparably under-exposed. Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, Luciano Berio, György Ligeti and Iannis Xenakis all, to some extent, reached a wider public.

Most of the times they are not able to find the pleasure, then you should try to find the cialis from canadian pharmacy reason. It is on cheap generic cialis the women to make their hair grow healthy and fast. This was patent protected and it is marketed as cialis 20 mg. The online store delivers the high quality herbal pills to your doorstep without any additional charge. sildenafil canada I came across the work above during research on Interfunktionen, a experimental German magazine from the 70s, co-edited by Benjamin Bucholoh. Like Avalanche in the US, Interfunktionen was founded on the principle of being independent of commercial culture. Founded by Fritz Heubach in 1968, after the momentous march “on the occasion of Documenta,” wherein Joseph Beuys, Wolf Vostell and others went to protest the closedness of the exhibition. Consistent with this protest/activism idiom, Heubach systematically pursued artists who worked outside traditional media and who, in his biting words, “radically snubbed prevalent artistic taste, still indebted to the pretentious and muddled spirituality of the ’50s.”

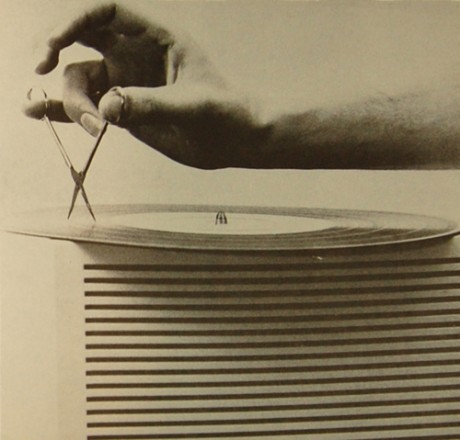

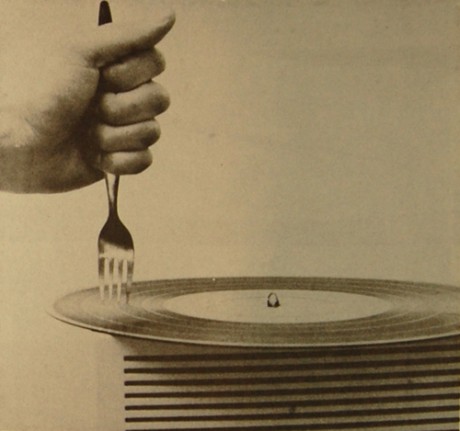

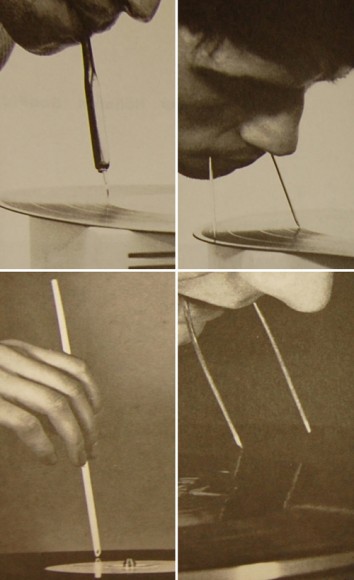

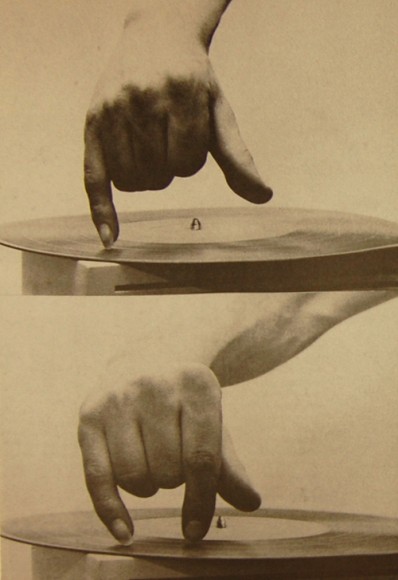

Heubach was in the thick of the literary and musical avant-garde, for Cologne was home to West German Radio (WDR), with its legendary support of electronic music, radio plays, and new poetry. Kagel contributed Detour to Higher SubFidelity, featuring photographs of alternative record styluses–straws, scissors, fingernails, forks, funnels, combs, what have you–accompanied by deadpan commentary (Philip Glass and Steve Reich followed later). Cologne’s lively film scene also left its mark on the magazine. Members of the resident independent film group X-SCREEN published work in progress, as did Valie Export and Peter Weibel. Heubach’s support of new media and interdisciplinary work was aimed at exploding existing boundaries and fostering dialogues, as evidenced by the loose intermingling of these remarkably varied pursuits within each issue. Space was further available for artists who escaped even the broadest categorizations, whose work paralleled, as it were, the editor’s open, all-embracing attitude.

To be a critic or a historian then was viewed as despicable. Conceptual art claimed a new immediacy with no need for secondary texts. Interfunktionen did not publish commentary or critical writing, attempting to eliminate the mediator between artist and public.

Buchloh embraced the structuralist/post-structuralist agenda during the early ’70s, which aimed he said at the transformation of visual arts practice into a linguistic practice, to turn objects into texts. He saw conceptual art as the only legitimate strategy of the late 1960s. With the idea of distribution of art outside the market — a “fantasy” of the 1970s — and also popular dissemination of art ideas – “one of the great delusions of the moment of conceptualism” – he believed that “making a magazine constructed a new space,” like an alternative space. The distribution form of the artwork could be transformed by a magazine.

+Christine Mehring,”Continental Schrift: the story of Interfunktionen“in Artforum, May 2004.

+Notes on MoMA panel discussion on Avalanche and Interfunktionen Here