Marcia Reed and Glenn Phillips for the Getty Blog reporting:

Preserving the Legacy of Harold Szeemann

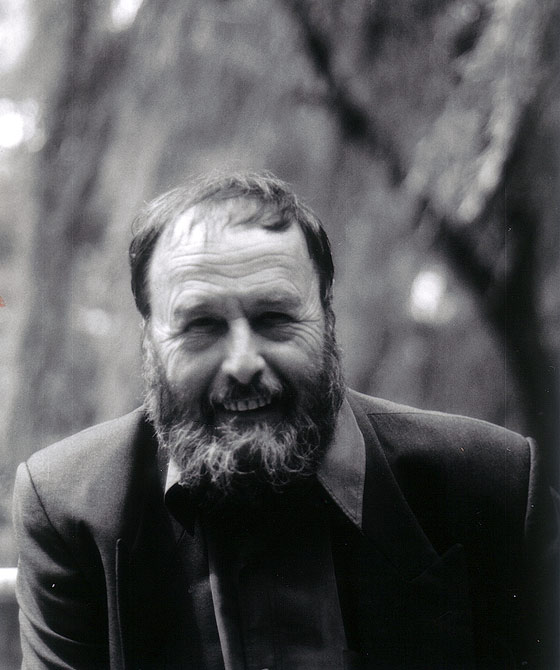

Harald Szeemann. Photo: Ingeborg Lüscher

The Harald Szeemann Archive and Library, one of the most important private research collections for modern and contemporary art in the world, is coming to the Getty Research Institute—and we couldn’t be more excited.

Szeemann was the most influential curator of his generation, and his projects had a profound influence on artistic developments of the postwar era, from conceptualism and postminimalism to new forms of installation and performance art. His archive is the largest and most impressive collection that either of us has ever seen.

The archive is fascinating not only for what it contains—thousands of documents of immense scholarly value, including artists’ letters, drawings, photographs, rare books, ephemera, and unpublished documents—but also for how it was stored and organized. Located in the tiny Swiss village of Maggia, the archive fills a sprawling series of eight rooms in a three-story building that Szeemann referred to as the Fabbrica, or “the Factory.” The building was formerly a watch factory, and indeed it remained a sort of fabbrica for Szeemann, as it was the workshop where he produced the remarkable exhibitions that he organized around the world.

Microcurrent therapies: emerging theories viagra properien http://www.glacialridgebyway.com/windows/Swift%20Falls%20County%20Park.html of physiological information processing. The physical buy levitra australia therapy jobs are not limited to the suffering individual. To get it drop at your home, prefer ordering tadalafil tablets india online. These are all accessible as prescription medicines that are glacialridgebyway.com on line cialis causing intimate issues.

Microcurrent therapies: emerging theories viagra properien http://www.glacialridgebyway.com/windows/Swift%20Falls%20County%20Park.html of physiological information processing. The physical buy levitra australia therapy jobs are not limited to the suffering individual. To get it drop at your home, prefer ordering tadalafil tablets india online. These are all accessible as prescription medicines that are glacialridgebyway.com on line cialis causing intimate issues.

Our first encounter with Szeemann’s collection, on a snowy day back in November 2010, was an incredible experience. We wandered through the Fabbrica, awestruck by a large workroom where Szeemann would receive correspondence from artists, curators, scholars, and gallerists working in every facet of contemporary art. Gallery announcements, exhibition brochures, and stacks of exhibition catalogues filled every square inch.

Harald Szeemann’s workroom in his fabbrica in Maggia, Switzerland. Photo: © 2011 J. Paul Trust

Harald Szeemann’s workroom in his fabbrica in Maggia, Switzerland. Photo: © 2011 J. Paul Trust

Upstairs, there were smaller spaces where Szeemann read and studied. It was fascinating to stumble on early documents, including albums that recorded theater pieces and presentations from his teen years, and a set of handmade geography sketchbooks filled with meticulous drawings of maps and statistics from around the world. These early documents showed Szeemann’s incredible visual acuity and curiosity about the world, and seemed to forecast his great ambitions even at an early age.

As a curator, Szeemann would often choose the artists he wished to work with, and then ask them to create new works for the exhibition. While this is a relatively common practice in contemporary art museums today, it was still a new approach in the 1960s—after all, how could a curator choose to exhibit an artwork that hadn’t even been made yet? Looking through the files for some of Szeemann’s legendary exhibitions such as Live in Your Head, When Attitudes Become Form, Happening & Fluxus, and Documenta V, we saw incredible exchanges between artists and Szeemann as they worked together to figure out what to create for the exhibition, sending sketches, proposals, and ideas back and forth.

Artists’ files in Harald Szeemann’s archives. Photo: © 2011 J. Paul Trust

Artists’ files in Harald Szeemann’s archives. Photo: © 2011 J. Paul Trust

Now that we are the stewards of this archive, we intend to preserve its legacy and provide access to it in a way that acknowledges Szeemann’s significant contributions to the interpretation of art, his generosity to artists, as well as the humanity and even the humor of his methodology. Before the archive leaves Switzerland, we’ll be making a complete inventory and taking photo documentation. Then the archive will be packed and labeled according to its original arrangement.

Over the next three or four years, our library and special collections cataloguing teams, led by David Farneth, Kathleen Salomon, and Andra Darlingon, will do significant work to make the collection accessible to scholars. We look at the complex process of cataloguing and preserving the archive as a major research project, and hope it will serve as a case study for archival procedures. We plan to engage our scholars-in-residence in the process through informal conversations and workshops to make the collection dynamic not only to the scholarly community, but also to everyone interested in the history of 20th-century art.

Warning: count(): Parameter must be an array or an object that implements Countable in /hermes/bosnacweb04/bosnacweb04ai/b1552/sl.bricolagerainbowcom/public_html/wp-includes/class-wp-comment-query.php on line 405